Friedrich Ebert

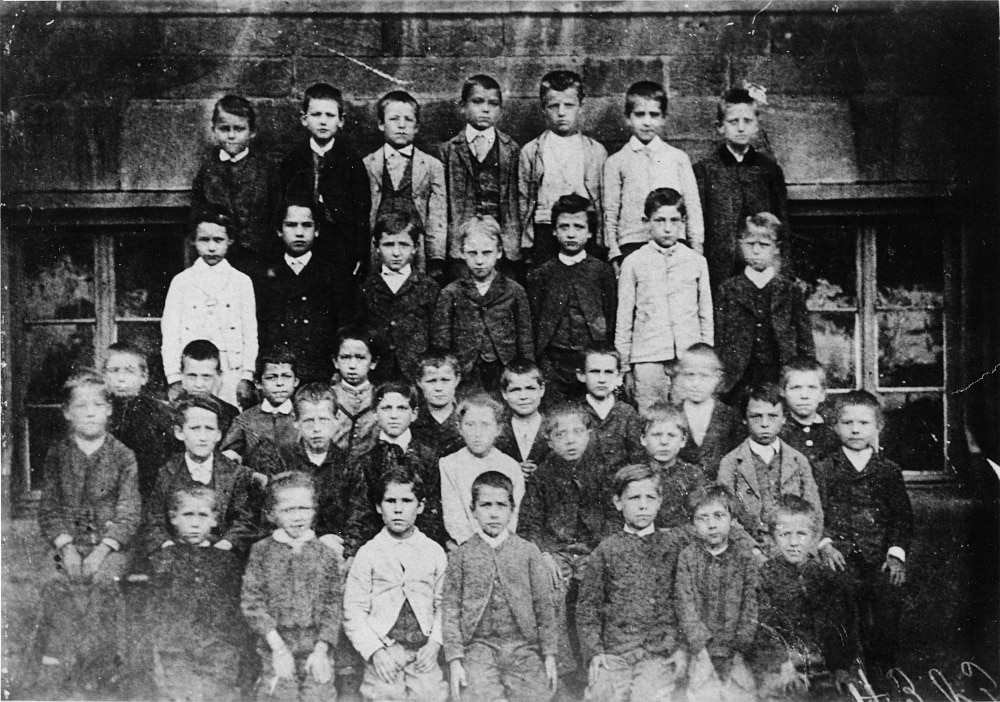

Birth and Early Years

Friedrich Ebert was born in Heidelberg on 4 February 1871. He completed both early schooling and saddlery training in his hometown. It was during his subsequent travels throughout Germany that he would become involved in Trade Unionism before joining the Social Democratic Party in 1889, later settling down in Bremen.

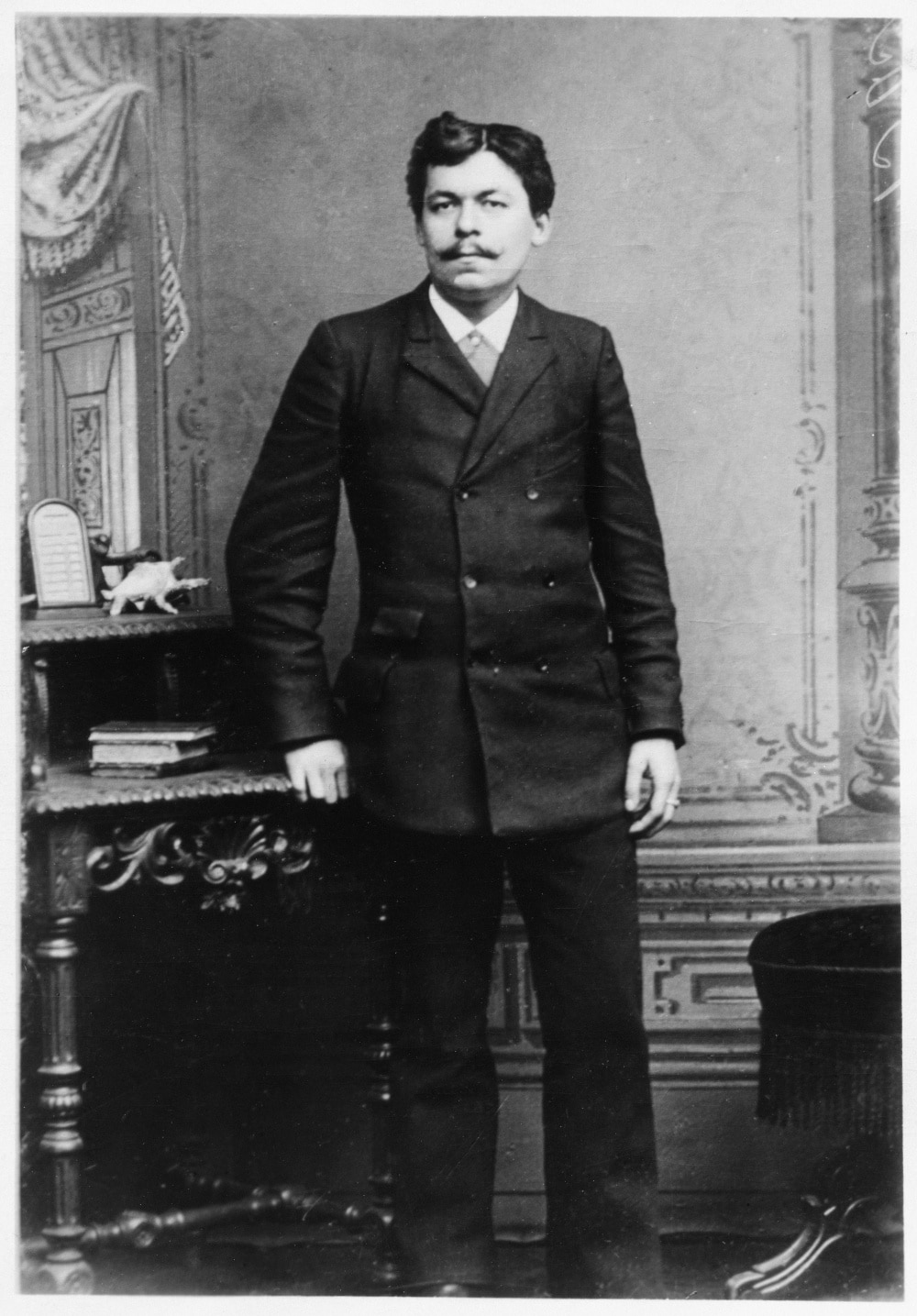

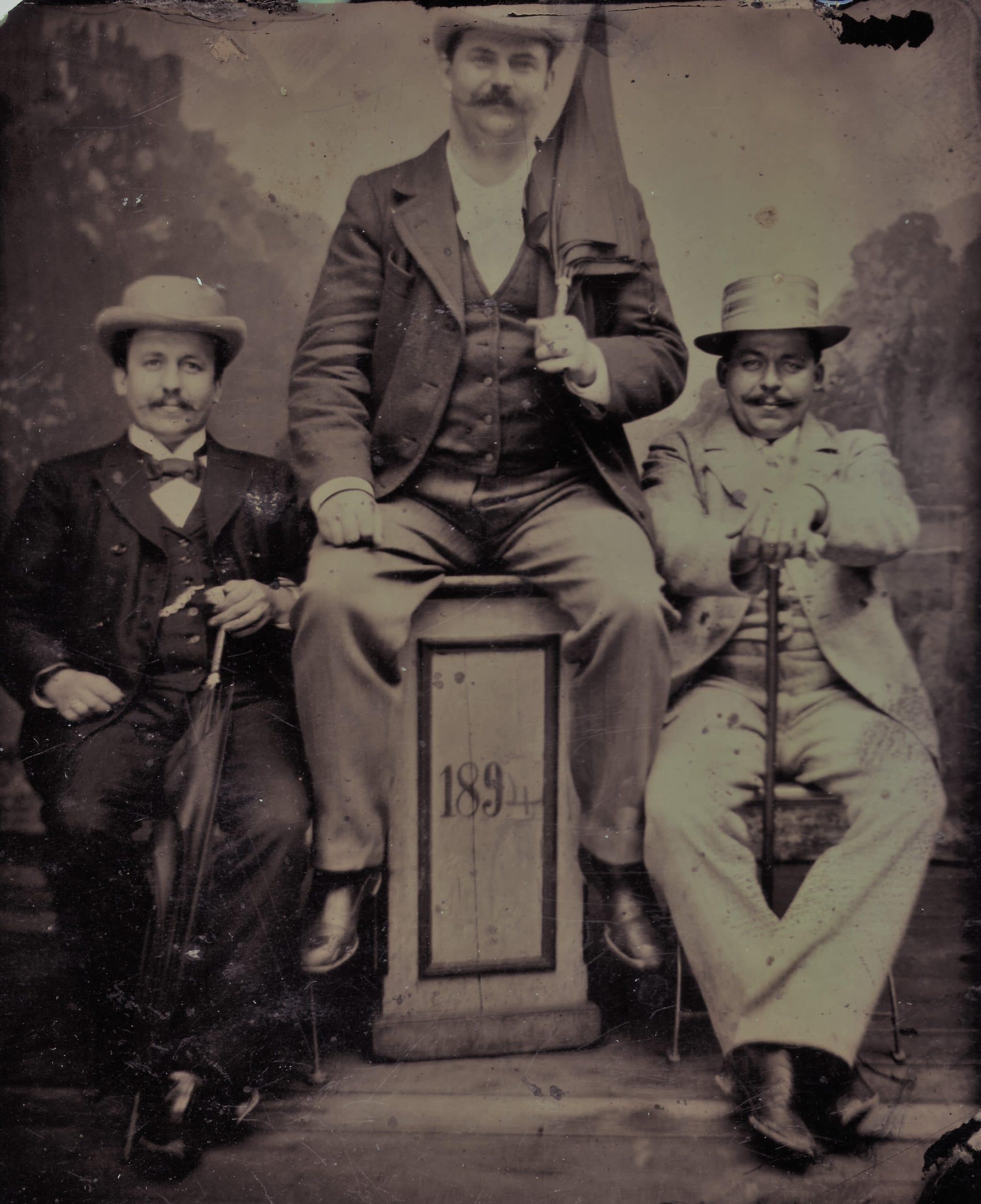

Friedrich Ebert in Bremen

Starting in 1894, Ebert would run a beer tavern for six years, where he would advise local workers on questions of social and labor rights.

That same year he married a working-class woman, Louise Rump, with whom he had four sons and a daughter. From 1900 to 1905 he worked as a representative in the Bremen city council. During that time, he also worked as what was then known as a Worker’s Secretary, advising workers as to their rights.

In 1904 Ebert would organize the SPD party council in Bremen. While during the previous year the party council had been marked by extreme controversy, meetings in Bremen would represent harmony and nearly perfect organization. Ebert would garner a reputation of efficiency and order through these meetings, leading to his nomination to the SPD central office in Berlin.

Social Democracy

In September 1905, Ebert was elected to the SPD party executive— at 34, he was the youngest member. In 1912 he was nominated into the Reichstag (the parliament of the German Empire), serving until 1918. In 1913 he was elected as one of the two Party Chairmen. It was through this position that Ebert would lead the SPD through the First World War, an affair that brought more than the just the SPD to the brink.

The First World War

In 1914, the SPD voted in favor of implementing War Bonds. It was a decision which was heavily disputed within the party, eventually leading to a split. The war also weighed heavily on Ebert’s personal life as two of his sons would die in 1917 on the front line. During a munition workers’ strike in January 1918, Ebert had himself elected to the strike committee with the hope of playing a mediative role, for which he would be later reproached.

The Revolution of 1918/1919

Friedrich Ebert would take on enormous responsibilities during the coming hard times. On 9 November 1918 he would take over affairs of state from Reichskanzler (chancellor of Imperial Germany) Prince Max von Baden.

In the revolutionary Council of People’s Representatives, Ebert would play an important role in establishing the first German democracy, while at the same time working to avoid a civil war. It was around this time that he began advocating for elections to a National Assembly. From this constitutional convention, he would be elected as president of the German Republic on 11 February 1919. In 1922, the Parliament would extend his time in office until 30 August 1925.

Friedrich Ebert as President

As President, Ebert held an important role in establishing and stabilizing the young Republic. The negative effects of the Treaty of Versailles, the demobilization of the military, and a diverse array of economic, international, and domestic crises brought with them an enormous series of challenges to overcome. Ebert saw himself as a President of all Germans, advocating for reconciliation and cooperation between the varying parties. Above all else, political stability was his aim.

Under Threat from Right and Left

These activities made Ebert a target for forces on both the radical right and left. In 1921, right-wing extremists assassinated Finance Minister Matthias Erzberger before killing the Foreign Affairs Minister Walther Rathenau a year later. Ebert, too, would be repeatedly challenged, attacked, and slandered. He would defend himself through legal channels, but due to these lawsuits and other legal matters, was forced to postpone an important surgery.

Death

Friedrich Ebert would die on 28 February 1925 due to complications with an undiagnosed appendicitis and his burial took place on 5 March in Heidelberg, drawing huge crowds. Ebert’s death weighed heavily on the young democracy and the election of Paul von Hindenburg brought a Monarchist and outspoken opponent of Republicanism to the head of the state. That day, the Weimar Republic lost her strongest guarantor — and Germany, her first democratically elected Head of State.